|

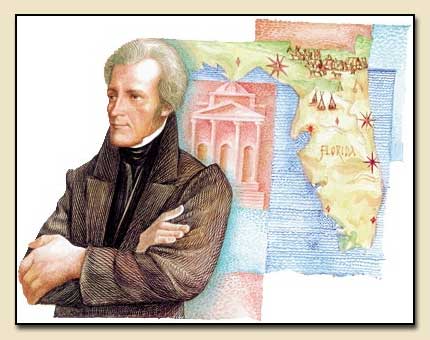

For protection, the citizens of southern Louisiana looked to Major General

Andrew Jackson, known to his men as "Old Hickory." Jackson arrived in

new Orleans in the late fall of 1814 and quickly prepared defenses along the

city's many avenues of approach.

Meanwhile, the British armada scattered a makeshift American fleet in Lake

Borgne, a shallow arm of the Gulf of Mexico east of New Orleans, and evaluated

their options. Two British officers, disguised as Spanish fishermen, discovered

an unguarded waterway, Bayou Bienvenue, that provided access to the east bank of

the Mississippi River barely nine miles downstream from New Orleans. On December

23 the British vanguard poled its way through a maze of sluggish streams and

traversed marshy land to emerge unchallenged an easy day's march from their

goal.

Two American officers, whose plantations had been commandeered by the British,

informed Jackson that the enemy was at the gates. "Gentlemen, the British

are below, we must fight them tonight," the general declared. He quickly

launched a nighttime surprise attack that, although tactically a draw, gained

valuable time for the outnumbered Americans. Startled by their opponents'

boldness, the British decided to defer their advance toward New Orleans until

all their troops could be brought in from the fleet.

Old Hickory used this time well. He retreated three miles to the Chalmette

Plantation on the banks of the Rodriguez Canal, a wide, dry ditch that marked

the narrowest strip of solid land between the British camps and New Orleans.

Here Jackson built a fortified mud rampart, 3/5 mile long and anchored on its

right by the Mississippi River and on the left by an impassable cypress swamp.

While the Americans dug in, General Pakenham readied his attack plans. On

December 28 the British launched a strong advance that Jackson repulsed with the

help of the Louisiana, an American ship that blasted the British left flank with

broadsides from the river. Four days later Pakenham tried to bombard the

Americans into submission with an artillery barrage, but Jackson's gunners stood

their ground.

The arrival of fresh troops during the first week of January 1815 gave the

British new hope. Pakenham decided to cross the Mississippi downstream with a

strong force and overwhelm Jackson's thin line of defenders on the river bank

opposite the Rodriguez Canal. Once these redcoats were in position to pour flank

fire across the river, heavy columns would assault each flank of the American

line, then pursue the insolent defenders six miles into the heart of New

Orleans. Units carrying fascines -- bundled sticks used to construct

fortifications -- and ladders to bridge the ditch and scale the ramparts would

precede the attack, which would begin at dawn January 8 to take advantage of the

early morning fog.

It was a solid plan in conception, but flawed in execution. The force on the

west bank was delayed crossing the river and did not reach its goal until well

after dawn. Deprived of their misty cover, the main British columns had no

choice but to advance across the open fields toward the Americans, who waited

expectantly behind their mud and cotton-bale barricades. To make matters worse,

the British forgot their ladders and fascines, so they had no easy means to

close with the protected Americans.

Never has a more polyglot army fought under the Stars and Stripes than did

Jackson's force at the Battle of New Orleans. In addition to his regular U.S.

Army units, Jackson counted on dandy New Orleans militia, a sizable contingent

of black former Haitian slaves fighting as free men of color, Kentucky and

Tennessee frontiersmen armed with deadly long rifles and a colorful band of

outlaws led by Jean Lafitte, whose men Jackson had once disdained as

"hellish banditti." This hodgepodge of 4,000 soldiers, crammed behind

narrow fortifications, faced more than twice their number.

Pakenham's assault was doomed from the beginning. His men made perfect targets

as they marched precisely across a quarter mile of open ground. Hardened

veterans of the Peninsular Campaign in Spain fell by the score, including nearly

80 percent of a splendid Scottish Highlander unit that tried to march obliquely

across the American front. Both of Pakenham's senior generals were shot early in

the battle, and the commander himself suffered two wounds before a shell severed

an artery in his leg, killing him in minutes. His successor wisely disobeyed

Pakenham's dying instructions to continue the attack and pulled the British

survivors off the field. More than 2,000 British had been killed or wounded and

several hundred more were captured. The American loss was eight killed and 13

wounded.

Jackson's victory had saved New Orleans, but it came after the war was over. The

Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812 but resolved none of the issues

that started it, had been signed in Europe weeks before the action on the

Chalmette Plantation.

-A. Wilson Green is the former manager of Chalmette National Historical Park.

|